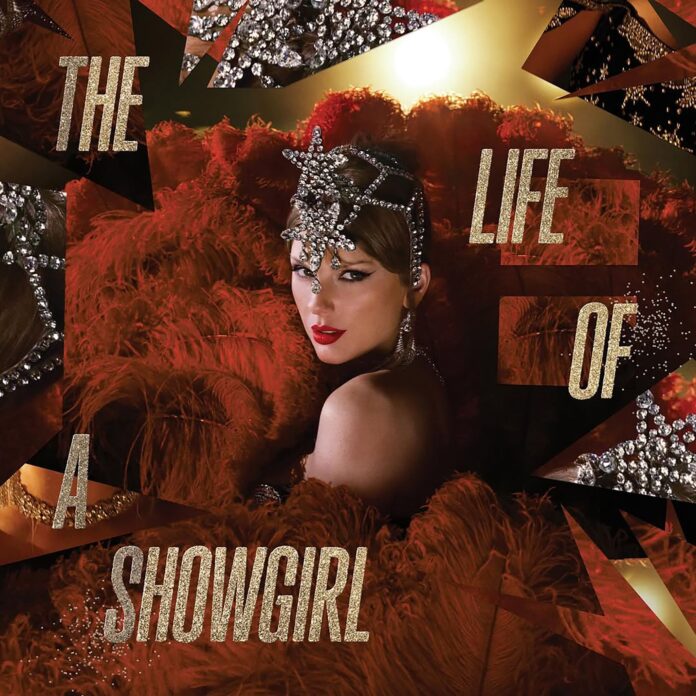

by Mara Taylor

There’s a sound you’ve heard before. A chord progression that hovers like déjà vu. The drum hits just the way you expect them to. The melody resolves in a place your body already knows. Taylor Swift’s new album, The Life of a Showgirl, is built entirely on that feeling: on the faint shock of recognition. It’s an album that sounds like other albums, a pop record made of pop itself. Not stolen, exactly. More like borrowed from the cultural ether, recycled through the machine of someone who’s been too famous for too long to hear the difference.

The controversies came fast, as they always do. “Actually Romantic” sounds like the Pixies’ “Where Is My Mind?”—and not just a little. The haunting, off-balance guitar line, the phrasing, even the emotional weight. Other tracks echo The Jackson 5, the Jonas Brothers, even herself. “Taylor Swift plagiarized the Pixies,” the headlines screamed. But maybe the more interesting question is why it doesn’t matter anymore.

Because The Life of a Showgirl isn’t about originality. It’s about permanence, the endurance of the pop loop, the copy of the copy that becomes the hit. Swift’s genius, if we can still call it that, has always been to repackage what everyone already feels, but prettier. She has built an empire on the repetition of emotion: heartbreak, revenge, survival, heartbreak again. The new album extends that formula to sound itself. She’s no longer just rewriting her own stories; she’s rewriting the shared archive of pop.

But let’s be fair: this isn’t a Swift problem, not really. It’s an industry problem. Pop music, like capitalism itself, thrives on imitation. The system rewards familiarity, not innovation. If something works, it works again. And again. Every hit song is a proof of concept: people like this. The machinery keeps turning. The producers—Max Martin, Shellback, the usual suspects—don’t so much compose as engineer feelings with proven metrics. They know exactly how much of the past to slip into the present to make it feel inevitable.

Swift has simply become the most efficient vessel for this logic. She embodies the smooth continuity of pop memory, where influence and theft blur into a single gesture of recognition. When fans say, “This reminds me of something,” that’s the point. It’s nostalgia weaponized as rhythm. And while critics cry “plagiarism,” the lawyers yawn. Pop has no originality clause, only market share.

Still, there’s something particularly cynical about how Swift performs this cycle. Because she has the power to transcend it, and doesn’t. The Life of a Showgirl is the sound of someone who could afford to disappear but chooses to stay. She’s not the hungry songwriter of Red or 1989 anymore; she’s the CEO of an emotional brand. Each track feels calibrated for maximum engagement, every melody designed to activate an echo from something you loved before. It’s nostalgia by design, sentimentality with an NDA.

And yet, it works. The album is good—frustratingly good. Catchy, textured, impeccably mixed. It doesn’t move pop forward, but it doesn’t have to. Swift’s job isn’t to innovate. It’s to reassure. To remind us that the world still makes emotional sense in four chords and a bridge. To sell us the illusion that feelings are renewable resources, that nothing is ever really lost if you can hum it again.

There’s a deeper cultural logic at play here. The sameness of modern pop mirrors the sameness of modern life: algorithmic feeds, predictable outrage, the recycling of nostalgia as comfort in a world that keeps erasing itself. When Swift borrows from the Pixies, she isn’t stealing from them; she’s participating in a collective cultural amnesia that turns every song into a reference. Music becomes a form of citation, a Spotify playlist pretending to be art.

From a sociological view, this is the perfect soundtrack to late capitalism’s emotional fatigue. The melodies are familiar because the emotions are pre-approved. We don’t want surprise; we want recognition. The thrill of déjà vu is safer than the shock of the new. Swift gives us what we crave: not innovation, but repetition with better lighting.

The irony, of course, is that she’s the only one who could break this cycle. But power, in pop as in politics, dulls the edges of rebellion. Swift no longer writes from the margins—she is the mainstream. And it’s always unfair to punch down. Her lyrical feuds and pointed songs about exes once felt cathartic; now they read as corporate tantrums. You can’t be a billionaire and play the underdog. But that contradiction is also part of the performance. It’s the illusion that keeps the audience on her side: the superstar as sufferer, the richest woman in music as the eternally heartbroken girl.

So yes, The Life of a Showgirl sounds like other songs. It borrows, blends, repeats. It plays the same game everyone else plays, only louder and better funded. But that doesn’t make it worthless. In a way, it’s the perfect mirror of our times, a collage of recycled feelings that still, somehow, hits a nerve.

Because even if the melodies are borrowed, the emotion they trigger is real. Even if Swift no longer surprises, she still captures something essential about how people consume meaning now: quickly, collectively, with the faint comfort of recognition. The music doesn’t need to be new to feel true.

Maybe that’s what pop is now: not invention, but persistence. The song you already know, reimagined just enough to make you listen again. Swift isn’t plagiarizing the Pixies; she’s plagiarizing memory itself. And that, in the end, is her greatest talent.