by Dan Cappo

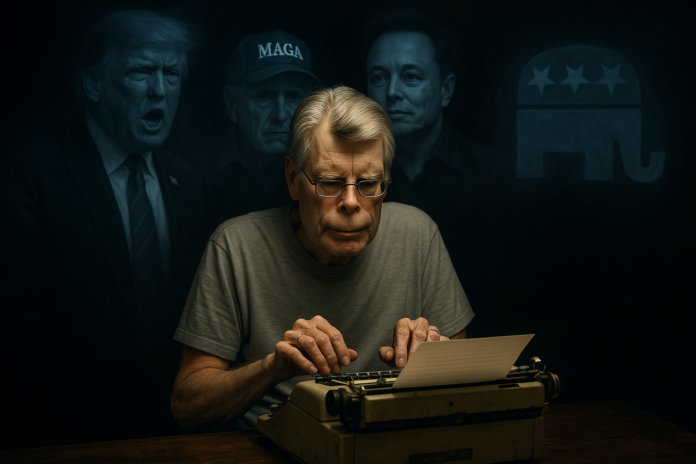

In Never Flinch (2025), Stephen King once again returns to Holly Gibney—his favorite late-career detective, and unlikely moral anchor. The novel is a thriller, ostensibly: Holly is pulled into a double plot involving a revenge-obsessed serial killer and a feminist speaker being stalked by a religious zealot. But beneath the page-turning mechanics is something more brittle, more telling. King isn’t just writing a mystery. He’s writing in anticipation of being misunderstood.

There’s a nervousness humming under every sentence of Never Flinch. Not narrative tension—King can still handle suspense in his sleep—but something more existential. The book’s villains are drawn with caricatured precision: Trumpist incels, evangelical creeps, broken men who channel their impotence into reactionary violence. And yet, the reader can’t help noticing how carefully everyone else is written. Kate McKay, the feminist speaker, is bold but sympathetic. Holly herself is still idiosyncratic but competent, her OCD now more virtue than burden. It’s as if King has built the entire novel on a tightrope strung between social consciousness and plausible deniability.

This isn’t new. Since around 11/22/63, King has increasingly blurred personal nostalgia with political liberalism, as though the Kennedy era could be reanimated and weaponized to fend off fascism and TikTok. For over a decade now, following Me Too—or perhaps anticipating it—in novels like The Outsider and Billy Summers, not to mention that one about the sleeping women he co-wrote with one of his sons, King has turned to a gallery of villains pulled straight from MSNBC nightmares: gun-worshipping white nationalists, YouTube fascists, men with barbed wire for souls and online followers to match. Sometimes it works. But often it feels like an aesthetic shortcut. These aren’t villains whose evil oozes slowly and seductively, as in It or The Shining. They’re evil because they watch Tucker Carlson and quote Jordan Peterson. They are wrong because they are wrong. The horror becomes less about what humans are capable of and more about the people King believes need to be stopped.

Meanwhile, the gender stuff hangs over all of it like a smoke alarm that won’t shut off. It’s impossible not to read Never Flinch in the long shadow of It—yes, that scene in the sewer, the tween orgy that King insists was meant as a symbol of unity. For decades he got away with it, protected by literary reputation and the horror genre’s infinite latitude for perversity. Now, in his seventies, he writes as if someone is finally going to call him on it. He writes like someone who has read the Twitter threads, seen the Goodreads backlash, and decided to get ahead of the noise.

So he writes feminists respectfully. He writes queerness obliquely. He writes villains that no one in his target demographic could possibly empathize with. He writes like a man trying to show his homework.

This isn’t to say Never Flinch is a failure. On the contrary, it’s skillfully plotted, briskly told, and surprisingly engaging in its final third. Holly is still a compelling presence—her blend of timidity and tenacity is one of the more honest things King has created in years. And the killer, Donald “Trig” Gibson, has moments of genuine psychological depth. He’s not a monster, exactly, but something much scarier: a broken man who believes the world owes him a body count. But even Trig is pressed through a cultural filter. He’s a MAGA brute with daddy issues and misogynist rage, and his ideology is never far from his weapons. King has stopped imagining evil. He’s started diagramming it.

There was a time when Stephen King’s villains didn’t need affiliations. They were ancient clowns, psychic vampires, abusive husbands with axes. They were scary because they were plausible, metaphysical, human. They came from within, not from cable news. But these days, King seems more concerned with being clear than being terrifying. In trying to be on the right side of the conversation, he’s begun to write as if afraid of being misunderstood—something fatal, perhaps, for a writer who once specialized in ambiguity, taboo, and dread.

The problem isn’t that Never Flinch is too political. King has always been political. The Dead Zone practically wrote the book on presidential precarity. Carrie is soaked in gender panic and religious violence. But in those books, the politics were baked into the horror. Now, the horror is an afterthought to the politics. The ideology leads, and the scares follow.

It’s tempting to see this as a late-career caution, the literary equivalent of a fading rock star doing a tribute album instead of a new one. But it’s more than that. It’s the fear of retrospection, of someone tracing the line from sewer sex in 1986 to a contemporary sensibility that no longer tolerates “symbolism” at the expense of ethics. King knows this. He reads the reviews. He tweets through it. He’s still writing, still publishing, still selling. But Never Flinch reads like a man checking his rearview mirror a little too often. And in fiction, as in life, that’s how you drift.

This is not a takedown. Never Flinch is better than most of what fills the bestseller list. King still has instincts other writers would kill for. But if you want to understand what happens when an author famous for fear becomes afraid himself—not of the monsters, but of the readers—this is the book. It’s not his worst. But it’s a mirror, held steady, and slightly trembling.

En español.