You don’t have to see it the first time. Or the second. In fact, you might not see it at all. Or you might pass right by it. After all, it’s transparent. By definition as much as by substance. At least the glass part is. The bars and fences aren’t transparent. But what brought you here in the first place points in the opposite direction. Toward the margins. Or around it. You’d have to twist your neck to see this other thing. And keep it twisted. Unless you already know what to look for. Because this isn’t a clandestine story. No insider secret. It could even count as an attraction. Something to photograph. Or somewhere to be photographed. Like a tourist site. And in any case, the specificity of its architectural function will dissolve among other signs of consumption. Or become part of the market experience. A total social fact. In the Maussian sense. Which is fascinating. Or could be. Too bad there are so many dead.

Costanera Center is a huge shopping mall—a mall, a shopping center, a retail complex, whatever it’s called where you’re from—like any other huge shopping mall. Same lighting. Same brands. Same materials. Same signage. Same planned paths. Same planned detours. But there’s something different. An element that doesn’t quite fit. That feels off. Until it stops feeling off and turns transparent. Part of everyday architecture.

The mall has seven floors, and on the railings that should function as balconies—places to rest your elbows or your hands and contemplate the spectacle of consumption—on the escalators, in any space that lets you lean over and look into the interior, there are anti-suicide barriers. Tall structures whose purpose is to prevent people from killing themselves by jumping into the mall’s central void. There’s a reason for that. Dozens of people have killed themselves by throwing themselves off inside Costanera Center. Dozens more have tried. And according to the story told by the tall barriers and the excessive number of security guards assigned to the task of tackling jumpers, dozens more are waiting for the chance to try. If the idea is to kill yourself in Santiago, the capital of Chile, Costanera Center isn’t just a good destination. It’s a better destination than most.

The mall opened in 2012. It’s the third largest shopping center in Latin America and part of a complex that includes the Gran Torre Costanera, a three-hundred-meter skyscraper, the tallest in the southern half of the continent, located in a high seismic-risk region where elevator small talk with strangers isn’t based on “Do you think it’ll rain?” but on “Did you feel the tremor this morning?” The complex sits in Providencia, an affluent area on the eastern side of Santiago, and belongs to the Cencosud business consortium. According to 2023 reports—the most or less corroborated ones—since its inauguration in 2012 there have been 73 suicide attempts: 49 unsuccessful and 24 completed. “Attempt,” according to these reports, refers to people who jumped into the void and died, or didn’t die, but did jump. The number doesn’t include those who didn’t make it to the jump. Because they changed their mind. Or because the barriers worked. Or because they were stopped beforehand. Put another way, 73 is a low number if what you’re trying to count is the real total of failed and completed suicides at the mall.

The theoretical underpinning of the anti-suicide barriers is also transparent. Transparent not in a utilitarian sense but in one that borders on pure cynicism. Maybe that’s why it stands out when applied to a shopping mall. It adds to the curious perception that killing yourself in a mall is an eccentricity, while throwing yourself off a bridge or a skyscraper or onto a subway platform is perfectly acceptable. According to this principle, the barriers are effective because people who attempt suicide by jumping from an elevated structure and fail to clear the barricade generally don’t try again—neither by jumping nor by any other means. But the barriers—say the urban planning and architecture textbooks as much as the sales catalogs of construction firms—keep the system running. They prevent interruptions in the transportation network. They prevent an area of the city that attracts suicides from losing real-estate value. They prevent a suicide from falling on you while you’re walking your dog and keeping you from fulfilling your social roles, like delivering a baby, trading stocks, or writing anthropology books. The barriers make sure that everyday activities—the train running on time, a nice street to live on, anthropology books, walking the dog—aren’t disrupted by the annoying intervention of someone who takes their suicide out of the decorous private sphere and turns it into a public event. These structures save lives, but they also safeguard the mechanisms of economic production.

At Costanera Center, this utilitarianism edging into cynicism finds a context that leaves it sitting right in front of the goalmouth of contemporary literature of indignation. It’s too obvious. Written in thick marker. Nothing subtle. Like something out of a George Romero movie. And again, fascinating. When someone manages to evade security, climb the barriers, jump into the void, and actually die, the mall’s protocol doesn’t include closing its doors. No alarm sounds. The building isn’t evacuated. No two days of mourning are declared. No one proposes a minute of silence. No one pretends to be surprised. Much less saddened. They don’t turn off the mall music. They don’t even close the level where the person fell. There’s a tent ready to be placed over the body so commercial activity doesn’t stop: it’s a nice neighborhood, the train runs on time, the bookstores stock anthropology books, dogs need to be walked, shopping has to continue. A common complaint among mall staff is that it takes too long to set up the tent over the suicide’s body. Until then, it lies there, next to the candy stand, across from the sneaker store, in front of shoppers sucking on a McDonald’s soft-serve cone and folding the specific event of a suicide into the total social fact of consumption. It’s a monument, Beatriz Sarlo wrote three decades ago, to a new form of civic life: “The shopping mall is all future; it builds new habits, becomes a point of reference, reshapes the city around its presence, gets people used to functioning inside the mall.”

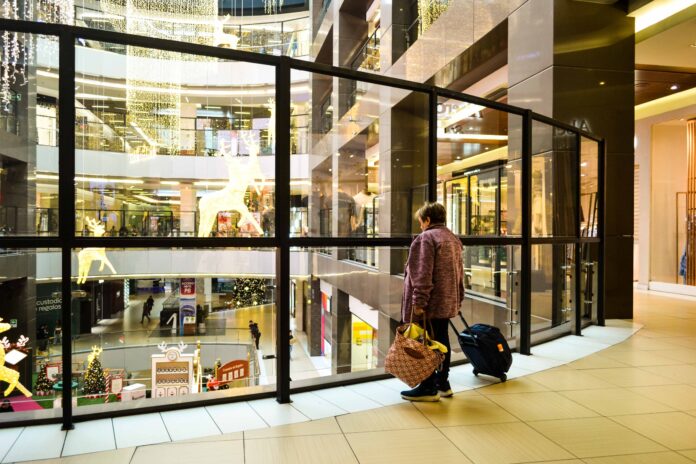

It’s Christmas season now. Decorations. Golden reindeer. Little trees. The cloying music. People accustomed to functioning in the mall. A city that takes it as a point of reference. And heightened suicide controls. No one wants to set up the tent on a freshly polished floor. Much less while listening to Mariah Carey. A security guard on one of the middle floors tells anecdotes about suicides he claims to have witnessed in the mall. He has them down cold. Some might be true. Others are already urban folklore. He says everyone dodges the night shift. Because you hear things. You see things. You feel things. Which makes sense. Costanera Center is a giant shopping mall, beneath the tallest building in the southern Americas, in an earthquake zone, a factory of new habits that in a decade has become one of the most attractive suicide locations on the planet. Of course it has a ghost story. Because it’s a total social fact. Nothing feels out of place. It’s transparent, and because it is, nothing is more opaque.