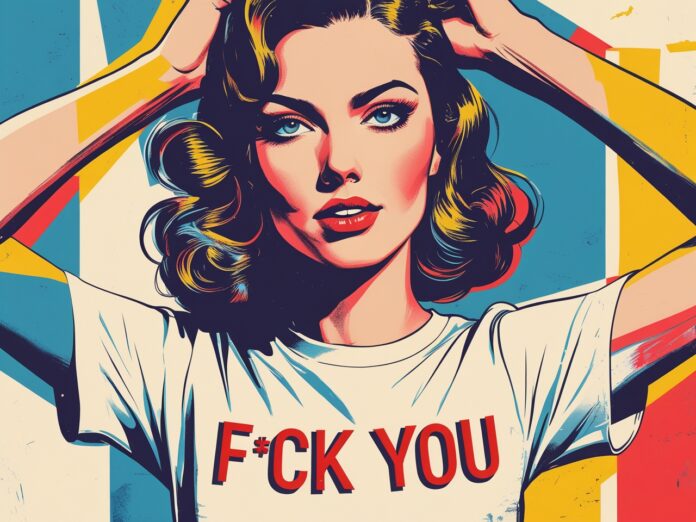

There’s this little song recorded by the British singer, songwriter, and occasional actress Lily Allen on her second album, and once you hear it, it’s impossible to get it out of your head. It’s called “Fuck You,” and it came out on It’s Not Me, It’s You, the album she released in 2009, when she was twenty-four and fun felt like clarity, clarity like wisdom, and wisdom like a consensual manipulation reduced to a bargain-bin trinket. “Fuck you, fuck you very, very much,” she sang cheerily in the chorus, a danceable, jubilant pop composition, a schoolyard taunt and, as such, deadly serious—built on repetitive structures, minimal variations, familiar harmonic landscapes, and a rhythmic texture that, as it stretches over time, convinces you there might actually be a chance to get away with it. Which, of course, is not true: that’s how all consensual manipulation works.

The song is innocent, sweet, brutal, stupid, charming, perfect, superficial, irresistible. It’s easy to dismiss it as a pop tantrum directed at someone vaguely objectionable, and impossible to avoid its grip on your auditory cortex on first listen, as effortlessly invasive as an alien slug mid-planetary conquest, like any good jingle for bubblegum. The song is less a venting than a diagnosis, the kind of ideological work usually reserved for theorists with compound surnames, unreadable books, and biographies that include a date of death. That Allen managed it in a little pop song says less about the lightness of the medium than about its structural capacity to produce hegemony.

“Fuck you, fuck you very, very much,” you keep humming, and there’s barely time to ask yourself how songs like this become part of our everyday patterns of meaning. What’s interesting isn’t that the song politely tells someone to fuck off (George W. Bush, according to Allen, who was president of the United States at the time), but the way the music shines without quite knowing why, that kind of gregarious joy that surrounds it, so much that it makes you forget it’s about telling someone to fuck off. So much that you don’t even care. It could be a song about cooking broccoli and it would feel the same. It’s too easy and too enormous. It should shatter the naturalized assumptions of your everyday life, and you wouldn’t even know how to begin formulating such a demand.

Something along these lines was written by German critic Diedrich Diederichsen in one of the essays in Personas en loop, his 2011 book compiling articles from the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, this one, the one that already burned through its first quarter and gave us songs like Allen’s: that, since the disappearance of the concept of counterculture, the enemy is the inner cretin, and the constitutive units of counterculture now drift, unmoored and ahistorical, through intricate cultural constellations.

He meant that from Allen’s song’s perspective—a song certified gold and platinum, one that, even now, here in the future, has 350 million streams on Spotify—counterculture is an epistemological joke, a conceptual disaster, a dead end for any attempt to rank meanings within social life. He meant that some elements deemed alternative or opposed to hegemonic culture, that promise to let us live, think, or feel otherwise, are appropriated, decontextualized, and turned into more precise tools of social coercion and control. That nothing can be considered countercultural in a social universe where counterculture is a constitutive part of what we call hegemonic culture. That politely telling someone to fuck off, with a bubblegum jingle melody, is a cultural rule, not a countercultural exception, because the countercultural exception is part of every cultural rule. That hegemonic culture and counterculture are simply culture, period. And that in this culture, songs about telling someone to fuck off provoke no perceptual friction, unlike, say, songs about cooking broccoli. Until five minutes later, once the song is over, it doesn’t matter much either way.

When you remember Allen’s song—not when you’re listening to it, but afterward, or before, thinking about it, humming it in your head, anticipating it, or putting it off—all this makes sense. Or it might not, at all.

What sets Allen’s “Fuck You” apart from other songs about telling someone to fuck off is its refusal to individualize the anger. Allen said she was talking to Bush Jr., but the song dodges that specificity. It functions as a floating signifier. It talks about xenophobia, homophobia, racism, fanaticism, but also about the strange joy with which all that is delivered. It talks about the smiling authoritarian, the polite fascist, the racist grandma offering you tea and cookies. The song humiliates sweetly more than it shouts truth with clenched fists; it doesn’t demand blood, or action, or commitment; it just withdraws affection. Its dramaturgy isn’t tragic or solemn, it doesn’t grieve a wound, it doesn’t complain, it doesn’t call for historical or political reparations, it doesn’t seek healing, it doesn’t want to raise a monument or place a commemorative plaque. What you hear is the sheer satisfaction of telling someone to fuck off for the simple pleasure of it.

By escaping the tropes of institutionalized protest, by sidestepping the idea that a song can change the world—or at least make it a bit fairer—“Fuck You” allows itself to be petty and vindictive without demanding anything in return (except, perhaps, that you buy the album). Allen isn’t leading a movement, and she’s certainly not asking you to follow her to the Bastille; at most, she’s leading a concert and forcing you to clap along. She doesn’t play the card of the contemporary outrage industry. She’s not trying to charm you. In fact, she comes off a bit unlikeable. She mocks the intellectual laziness of the intolerant, mimics their stupidity, and leaves them no way out. There’s no invitation to dialogue, no hope for transformation, no pedagogical mission. There’s a refusal to flatter the listener with a half-baked argument. That refusal is political and aesthetic. It’s also good entertainment. She’s not interested in your redemption arc. She cares that you don’t lose your narrative. That you don’t stoop. That you don’t take the bait disguised as discourse.

At its best, “Fuck You” makes intolerance seem uncool. Not monstrous, not repugnant, not even dangerous—just dumb, sad, outdated. It doesn’t respond to hate with moral superiority, but with ridicule. This is a tactic far older than protest songs. For centuries, cultures have used satire, imitation, and exclusion as mechanisms of symbolic containment, ritual tools of purging and moral control. Allen’s song belongs to that tradition. It crafts a musical dunce cap and places it squarely on the heads of those who think they’re in charge. It doesn’t expect them to change. It just wants to mock them.

The value of the song lies in its tonal play. The lyrics are acidic; the music wears a high-sugar-content label up front. That contradiction is what allowed it to circulate for the past fifteen years. You can play it at a party and see heads nod. You can play it at a protest and see fists rise. You can play it for the person you’d like to tell to fuck off—and chances are, they’ll sing along. With feeling. If power hides in the banal, the song suggests, resistance might do the same.

This version of resistance—Diederichsen might have called it countercultural, then put it in quotation marks, and finally discarded it in a footnote—requires no revolutionary fervor. Just contempt. In a time when every opinion must be respectable, “Fuck You” reclaims the insult as a political gesture: a banal form of rejection. A refusal to explain, to tolerate, to empathize with systems that don’t deserve it. It’s the strategy of stepping out of the game.

In many cultures, social death precedes physical death. Being mocked, excluded from the conversation, or denied the dignity of a serious response often destabilizes more than direct confrontation. Allen doesn’t open a debate; she makes the intolerant laughable, tells them to fuck off, and thanks them. That’s the edge where hegemonic culture, counterculture, and cultural constellations—Diederichsen’s terms—meet: humiliation as resistance. Not because it feels good (though it clearly does), but because it works.

In a world that demands the oppressed be reasonable, the song Lily Allen wrote fifteen years ago offers something else: an unreasonable anthem. A call to pettiness, a meaningless taunt, a playground trip followed by unrepentant laughter. Because sometimes, the song suggests, the most ethical thing you can do is be rude, and mockery, as an epistemological project, is the vehicle for an ethics of banality.